Hope Springs Eternal – The Ghost Dance

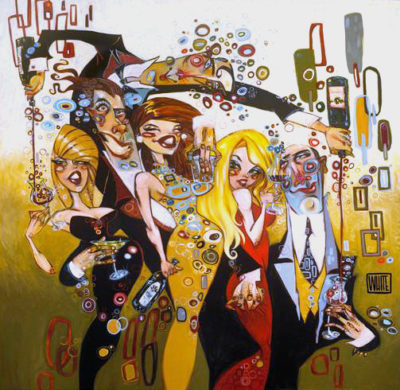

Artwork Description

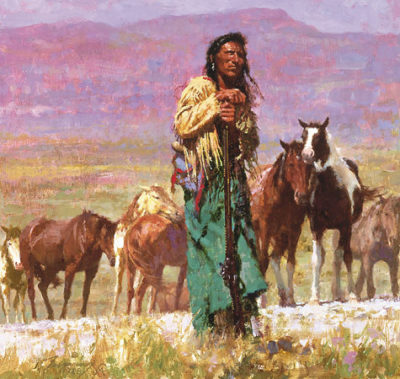

When Howard Terpning’s Hope Springs Eternal—The Ghost Dance was unveiled at the 1987 Cowboy Artists of American show, it was instantly recognized as a modern masterpiece. The scale of the 60” x 44” original provided the perfect platform to showcase the artist’s prowess with light, composition, balance and structure. At such a large size, the emotion and humanity spills out from his painting. It won both Cowboy Artists of America Oil Painting Gold Award and the Western Art Associates Best of Show Award.

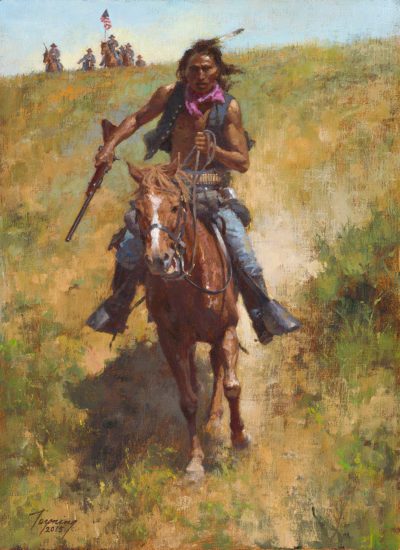

The 1876 defeat of Custer’s 7th Cavalry at Little Big Horn proved to be a Pyrrhic one for the Sioux and the Cheyenne as well as the Plains Indian culture. From that point on, it became a priority for the U.S. government to establish unquestioned control of the West.

The entire Plains Indian way of life came under attack with the intent to destroy it. Bison were no longer hunted for their hides, they were simply slaughtered. By 1881, most tribes had been hunted, harried and driven onto the harsh, unproductive lands sets aside as reservations. Confined, malnourished and stripped of their freedom and dignity, the suffocation of the Plains Indians and their culture was underway.

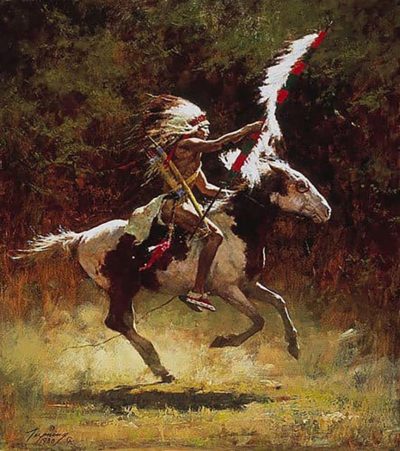

In 1889, a Paiute medicine man, while suffering a high fever, had a vision. In it, he journeyed to the afterworld and saw that those who had died in the past were living a happy life. He was told that through dance his people could regain the old ways that had been taken from them. The dance would resurrect the dead, bring back the buffalo and cause the white man to disappear. That his vision occurred during a solar eclipse only added to its significance.

The Ghost Dance swept the Plains like a wildfire and was embraced like a religion. The promise of a return to the life they had lost was a powerful intoxicant. As tribe after tribe entered the movement ― the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Shoshone, Comanche and Sioux ― the U.S. government became more and more concerned.

The dancers wore loose shirts and dresses that were adorned with feathers, fringe and symbols of the moon and stars. They moved in a counter-clockwise direction to the rhythm of drums, chants and songs. Handfuls of dirt were hefted into the air to symbolize the burial of the white man. As they danced some would fall into trances where they claimed to communicate with the dead. It was believed that the Ghost Shirts and Dresses they wore would be impervious to the soldiers’ bullets.

The Ghost Dance soon emboldened bands of Indians to leave their reservations and return to their old way of life. That was the beginning of the final end. The army hunted down those that left the reservations; leaders such as Sitting Bull were killed and finally, the violence culminated on December 29, 1890 with the massacre at Wounded Knee.

This work of raw spiritual emotion is one of Terpning’s most powerful tributes to the Plains Indian way of life. It is simply one of the finest works of art you could ever hope to possess.